What would you choose if a sudden arrest forced a split-second decision about life-saving treatment?

This guide explains what each option means for a patient in an emergency. In many U.S. hospitals, an undocumented preference defaults to full code so teams can act fast. That choice triggers all standard resuscitation steps: CPR, defibrillation, airway management, and ACLS medications.

Clear code status documentation aligns care with personal values and avoids ethical conflicts at the bedside. DNR/DNI orders limit resuscitation but do not stop routine or comfort care.

You’ll see how a status order guides the team in a hospital emergency, what interventions a full code response includes, and why clarity at admission protects patients and clinicians.

Key Takeaways

- Full code activates all life-saving interventions during arrest.

- Undocumented preferences often default to full code in hospitals.

- DNR/DNI limits resuscitation while preserving comfort and routine care.

- Clear documentation of code status reduces confusion and ethical conflict.

- Understanding interventions helps align status with patient goals.

Understanding Code Status Today: How U.S. hospitals define Full Code and No Code

Hospitals use a standing order to tell teams exactly how to act when a patient stops breathing or loses a pulse.

Code status orders instruct staff which resuscitation steps to take. Common categories include Full Code (all measures), DNR (no CPR/defibrillation), and DNI (no intubation). Each order changes what clinicians do in an emergency.

The chart displays the order prominently so any physician or nurse can act without delay. When a patient’s preference is not documented, many clinicians adopt a default Full Code to avoid delaying life-saving care.

| Order | What is limited | Routine care |

|---|---|---|

| Full Code | None — CPR, shocks, intubation allowed | All routine and comfort care |

| DNR | No CPR or defibrillation | Medications and symptom control continue |

| DNI | No intubation or mechanical ventilation | Other treatments and comfort care continue |

Document status on admission, after major changes, or before procedures. A patient may sign the order; if incapacitated, a legal representative usually can. Early conversations reduce confusion for families and the team and prevent ethical conflict.

For help planning these discussions and charting clear orders, see this advance planning resource.

no code vs full code medical: definitions, scope, and patient choices

Your documented choice determines if teams use chest compressions, shocks, breathing tubes, and advanced drugs during arrest.

Full Code: what is authorized

Full Code authorizes all resuscitation measures: CPR, AED shocks, intubation with mechanical ventilation, and ACLS medications.

That order enables immediate airway management and advanced cardiac drugs when needed. It is the operational instruction clinicians follow during a life-threatening event.

No Code (DNR/DNI): what is limited

DNR limits attempts to restart the heart — no CPR or defibrillation. DNI avoids intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Both types of orders still allow routine, symptom-directed, and comfort treatments. They do not withdraw other evidence-based care for the patient’s condition.

Patient autonomy, counseling, and legal documentation

Physicians should explain likely outcomes, risks, and how each choice fits a patient’s goals and quality of life.

Patients or legal proxies can set, update, or revoke an order. Accurate, accessible chart documentation prevents unintended interventions across shifts and teams.

- Crisp definitions so you know what each status permits.

- A clear outline of interventions enabled or restricted.

- Practical tips: prepare questions, ask about outcomes, and confirm where the order is recorded.

| Category | Allowed | Restricted |

|---|---|---|

| Full Code | CPR, defibrillation, intubation, ACLS drugs, routine care | None related to resuscitation |

| DNR | Routine care, symptom management, other treatments | CPR, defibrillation |

| DNI | Medications, noninvasive oxygen, comfort measures | Intubation, mechanical ventilation |

What actually happens during resuscitation: CPR, shocks, breathing tubes, and life support

When a patient arrests, the team follows a timed, choreographed set of interventions aimed at restoring circulation and breathing.

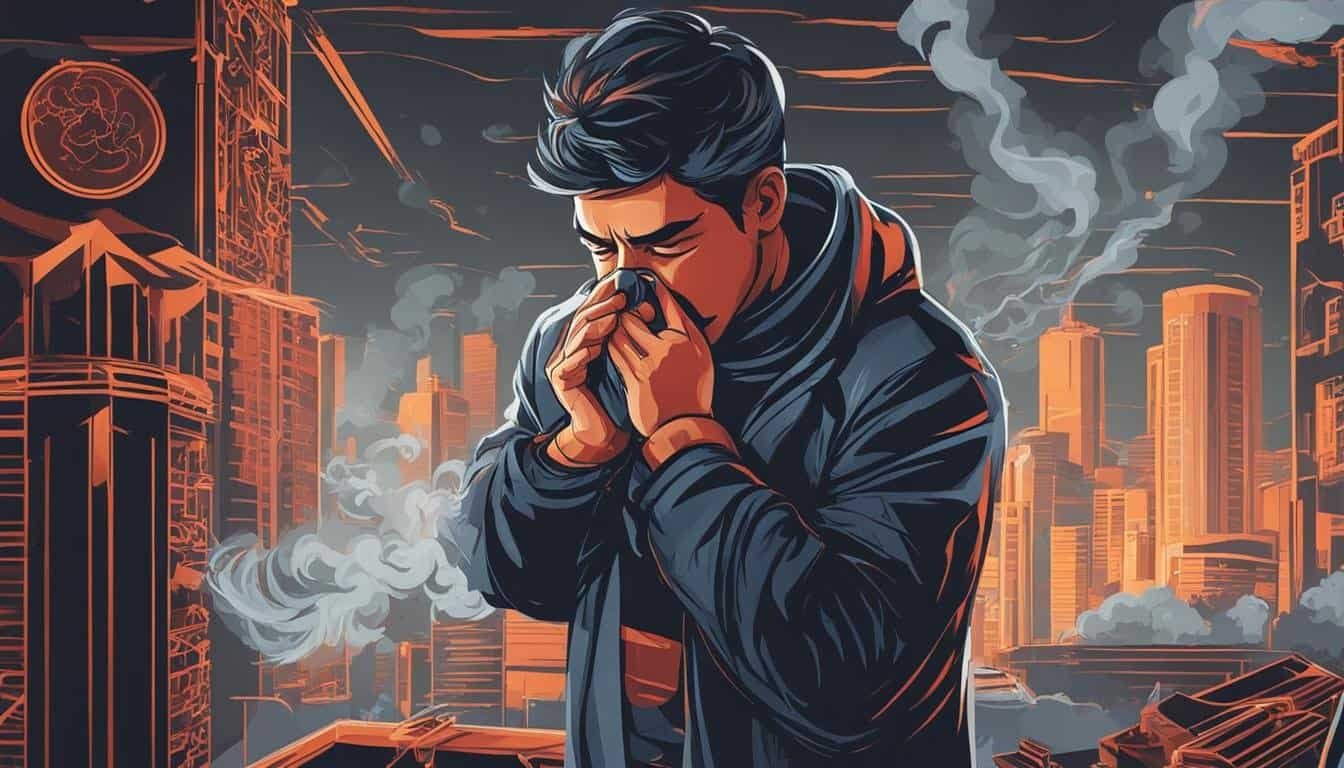

From activation to ICU handoff: a rapid sequence begins. Staff activate the code team and start high-quality cpr with forceful chest compressions. Compressions may continue for 30 minutes or more and can cause rib fractures in older or frail patients.

From chest compressions to ventilator support: step-by-step interventions

- Team starts cpr and assesses rhythm. If needed, a single or repeated shock is delivered.

- Doctors may perform intubation: a breathing tube is placed, the patient is sedated, and a ventilator provides respiratory support.

- ACLS medications such as epinephrine are given to support circulation while cardiac monitoring continues.

- Oxygen and ventilator settings are titrated in real time to stabilize gas exchange after return of circulation.

Complications can include airway trauma, chipped teeth, or rare hypoxic injury despite expert care. Documentation must record times, medications, procedures, and patient response. After return of circulation, the patient moves to ICU for ongoing life support and organ monitoring.

Outcomes, risks, and when aggressive care helps—or harms

Outcomes after an arrest vary widely; quick action and underlying health shape who survives.

Survival differs by setting. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival is roughly 12%. Early CPR can double or triple those odds.

In the hospital, adults who arrest have higher survival to discharge—about 17–20% in many reports.

Injuries and complications

High-quality chest compressions save lives but can cause harms. Rib fractures and airway trauma occur commonly.

Many survivors face prolonged ventilator dependence. Over 40% have significant functional decline after resuscitation.

Which conditions favor aggressive care

Reversible problems—like an acute arrhythmia or pneumonia—often respond to prompt treatment and life support.

By contrast, advanced illnesses such as metastatic cancer, end-stage renal, or liver failure lower survival to 5% or even under 1% in some studies.

How physicians weigh benefit and burden

Clinicians balance likely benefit against risks and patient goals. They explain probable outcomes and the chance of disability.

- Survival is higher in hospital but still limited and depends on timely CPR and support.

- Patient age and comorbid conditions drive outcomes more than any single intervention.

- Revisit choices as your condition changes to keep treatments aligned with your goals.

Comparing real clinical scenarios: cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, advanced cancer

Three situations highlight how the same order can produce very different treatments and outcomes.

Cardiac arrest on the ward: When the heart stops, teams call a rapid response and start compressions, airway maneuvers, rhythm checks, and ACLS medications. Defibrillation happens if indicated. If a pulse returns, patients usually go to the ICU for ongoing monitoring and organ support.

Respiratory failure from pneumonia: Breathing worsens and doctors prioritize airway support. Intubation and mechanical ventilation begin alongside antibiotics and vasopressors if pressure falls. If lungs recover, clinicians wean ventilation and extubate when safe.

Advanced metastatic cancer: An initial full code can lead to prolonged life support with low chances of meaningful recovery. Families and the physician often revisit the order to focus on comfort and symptom control when goals shift toward quality of life.

- Compare arrest: compressions, medications, shocks, ICU transfer if ROSC occurs.

- Compare respiratory failure: airway, ventilation, targeted treatments, then wean if reversible.

- Compare advanced cancer: aggressive support may prolong life with limited benefit; pivot to comfort care may follow family discussion.

You’ll learn the decision points that matter: likely outcomes, burdens of treatment, and what quality of life means for patients and families. Doctors should communicate options clearly so you and your loved ones can choose a path consistent with values.

| Scenario | Primary Early Treatments | Usual Trajectory | Key Decision Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrest | CPR, defibrillation, ACLS meds | Return of pulse → ICU; or no ROSC → termination | Likelihood of neurologic recovery |

| Respiratory failure (pneumonia) | Intubation, ventilation, antibiotics, vasopressors | Weaning and extubation if lungs improve | Reversibility of lung injury |

| Advanced metastatic cancer | Life support, symptom control | Often prolonged dependence with low recovery odds | Goals: longevity vs comfort |

For guidance on planning these conversations and documenting an order, see this advance planning resource.

Documentation, billing, and compliance for code events in U.S. hospitals

Every resuscitation event must leave a clear trail of who did what and when.

Why this matters: detailed records support clinical decisions, justify billing, and protect hospitals and professionals during audits. Capture the clinical context, exact date and time, team members, and the duration of cpr.

Essential elements to record

- Exact date and clock time for activation, interventions, and ROSC or termination.

- Names and roles of team members and the physician directing resuscitation.

- Procedures performed: cpr minutes, intubation, central lines, and other invasive actions.

- Medications given with doses and times (epinephrine, amiodarone, etc.).

- Patient response, disposition, and finalized order that documents goals of care.

Coding pitfalls, common denials, and best practices

Map services to core CPT codes: 92950 for cpr (one per event), 31500 for endotracheal intubation, and ventilation management (94002–94004) when used. Use critical care codes 99291–99292 only after separating active resuscitation minutes from post-resuscitation critical care time.

| Risk | Cause | Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Denial | Missing modifier or wrong diagnosis link | Add -25 when applicable; tie services to I46.9 or supporting diagnosis |

| Duplicate billing | Overlapping time for CPR and critical care | Document exact minutes for each activity and separate time blocks |

| Attribution error | Unclear performer for procedure | Record who performed intubation or other procedures by name and role |

Quick operational pearls: standardize code notes, run internal audits, and train physicians and professionals to document medical necessity. Defaults in an emergency should not replace a complete finalized order and billing record.

Making an informed choice with your care team and family

A short conversation now can prevent stressful decisions at the bedside later.

Talk with your doctors and families about likely outcomes, risks (rib fractures, airway injury), and the chance of ventilator dependence after resuscitation. Ask how treatments like chest compressions, shocks, or a breathing tube match your goals.

Focus on scenarios: reversible infections often respond to aggressive support, while advanced illness may favor comfort-focused life care. DNR/DNI orders can be updated or revoked as conditions change.

Document your code status clearly. Share copies with your physician, the hospital, and your families so emergency teams follow your wishes and avoid an unwanted default.