What would you want your medical team to do if your heart or breathing stopped—push every intervention or focus on comfort?

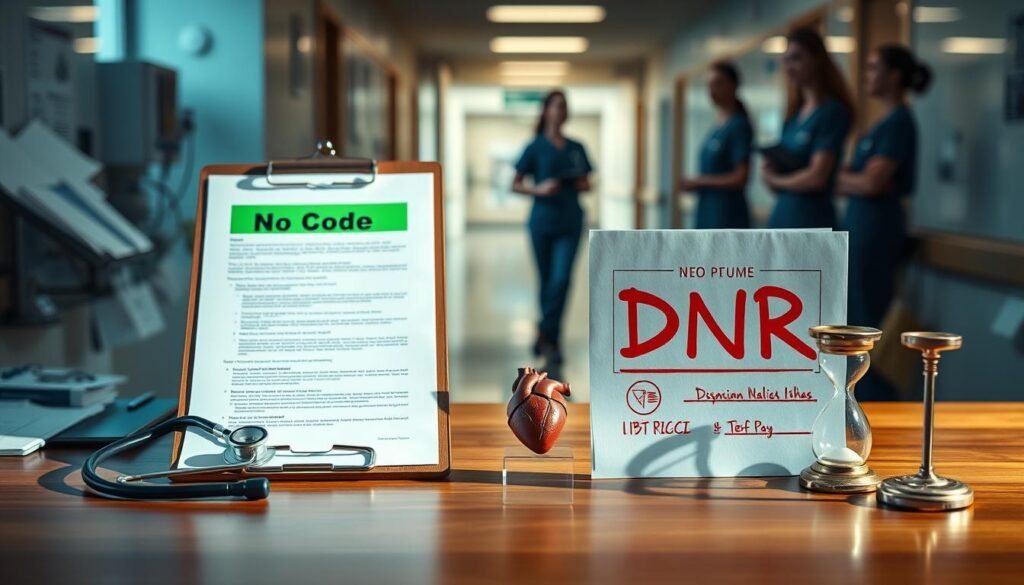

This section clarifies the difference between a formal no code vs dnr choice and how that affects patients in an emergency. A DNR order tells hospital staff not to attempt CPR if cardiopulmonary arrest happens.

In the hospital, CPR can include chest compressions, defibrillation, resuscitation drugs through an IV, cardiac monitoring, and often intubation with mechanical ventilation. Data show fewer than one in four patients survive to discharge, and odds fall with serious illness.

We compare these options so you can align your care with values and medical realities. You will see what doctors and a physician will do when the heart or breathing fail, and learn practical steps to make your wishes visible in the medical record.

For clear templates and extra information about documenting choices and out-of-hospital recognition, see the linked resource on health care forms and bracelets: no-code healthcare solutions.

Key Takeaways

- DNR affects only CPR at arrest; it does not mean you stop receiving other treatments.

- Hospital CPR includes compressions, shocks, meds, and often intubation.

- Survival after in-hospital CPR is limited and worse with advanced illness.

- States differ in how orders work; official forms and bracelets help EMS honor wishes.

- Discuss options with your physician and document your decisions before an emergency.

Defining code status, DNR, and what “no code” means in the hospital

Code status is the set of instructions clinicians follow when a patient’s heart or breathing stops. It specifies whether teams should begin CPR, use electrical shocks, give resuscitation drugs, or place a breathing tube for life support.

What code status covers

In practice, the team may perform chest compressions to circulate blood and attach monitors to guide rhythm decisions. When indicated, staff deliver defibrillation and IV medications to try to restart the heart.

CPR in real life

CPR is a sustained effort: repeated compressions, shocks when needed, and continuous cardiac monitoring. Effective chest compressions require force and can cause rib injury and chest pain if the patient survives.

What DNR/DNI means for patients and families

A DNR declines CPR; a DNI declines intubation. Both orders are entered in the medical record so every doctor and nurse follows the same measures. Other treatments—antibiotics, fluids, or comfort care—can continue if they match a patient’s goals.

- Your role: ask about likely benefits, expected recovery time, and pain or long-term support if resuscitation or intubation succeeds.

No code vs dnr: key differences, scope, and timing

Understanding exactly what an order allows or limits matters when the heart stops.

A DNR typically applies only to CPR and defibrillation. A broader "no code" declaration commonly implies limits on intubation or ICU care and must be translated into clear medical orders by a physician.

Scope of treatments

What is covered: DNR = decline CPR and shocks at arrest. Broader orders can add refusals for intubation, vasopressors, or ICU transfer. Discuss precise treatments with your physicians so the order reflects your options.

Timing distinctions

Some orders, like Ohio's DNR-CCA, allow aggressive treatment until the heart or breathing stops, then switch to comfort-only care. Ohio's DNR-CC limits comfort care at all times after entry.

State and portable orders

Florida uses a single DNR that declines CPR; pre-arrest limits need separate documentation. Portable forms, bracelets, and POLST let EMS and hospital teams honor your preferences across settings.

| Order type | When it applies | Common scope |

|---|---|---|

| DNR (Florida) | At cardiac or respiratory arrest | Declines CPR/defibrillation only |

| DNR-CCA (Ohio) | Before arrest and at arrest | Aggressive care before arrest; comfort-only after arrest |

| DNR-CC (Ohio) | At all times after entry | Comfort measures only before, during, and after arrest |

- Without visible identification, EMS will start resuscitation by default; place your form prominently and consider a bracelet for quick recognition.

- Portable orders like POLST are physician-signed and travel with you across settings.

For practical templates and job-related guidance on forms and health care documentation, see related forms and resources.

How these decisions affect care, comfort, and outcomes today

The immediate choice about resuscitation shapes what happens in an emergency and afterward. If CPR begins, teams aim to restore circulation and breathing. In-hospital data show fewer than two in four attempts restart the heart, and only about one in four patients leave the hospital alive. For more detailed survival data, see survival data.

Chances of survival, potential injuries, and time on a ventilator

Resuscitation can last 30 minutes or longer. Effective chest compressions are forceful and can break ribs or injure the chest. Even when circulation returns, people may face organ failure, cognitive decline, or long rehabilitation.

Intubation and ventilator care change daily life. Patients need sedation, cannot speak, and time on a ventilator ranges from days to months. Some never regain independent breathing.

“Do not resuscitate” is not “do not treat”: comfort measures and other treatments

A DNR order stops CPR at arrest but does not stop most other treatments. You can still receive antibiotics, transfusions, dialysis, or ventilator support if those match your goals.

Comfort-focused measures address breathing distress, pain, and anxiety to improve quality of life. Doctors tailor treatments and may offer time-limited trials to test benefit.

- Clear orders reduce confusion and help the hospital team act quickly.

- Discuss priorities—more time at home, fewer ICU days, or better symptom control—to guide choices.

- Use practical tools and templates to document wishes, such as the planning templates.

Choosing the path that aligns with your values and medical condition

Deciding how you want teams to act when the heart stops starts with clear values and simple medical choices.

Talk early with your physician and your surrogate about likely outcomes from CPR, intubation, and life support. Translate values into a written order so hospital staff and EMS can honor your wishes without delay.

Ask to see the order in the electronic medical record and confirm any wristband or portable form. Consider a POLST or state portable form and keep copies with family and in your wallet.

Use team resources—nurses, social workers, chaplains, and ethics consultations—to shape decisions. For practical guidance on advance planning and documenting end life preferences, see what doctors wish patients knew about end‑of‑life care.